Our time on Earth may be limited but our curiosity will always get the best of us despite our mortalities. The drive to explore what lies beyond this little rock we call our home is ever-present in humanity, and nothing speaks volumes about that more than NASA‘s new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The modern-day successor to the legendary Hubble Telescope, JWST, is by far the most advanced observatory ever sent into space. It cost $10 billion to create, is 30x more sensitive than Hubble, and was launched into space in just December of yesteryear. Today, it has given us its first-ever image, marking a historic moment in space and time.

In collaboration with U.S. President, Joe Biden, NASA revealed what is the first in a series of pictures taken by the James Webb Telescope showing the most distant parts of space in the highest detail possible. These are the earliest full-color images JWST has taken, and they were developed together with the help of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) and European Space Agency (ESA).

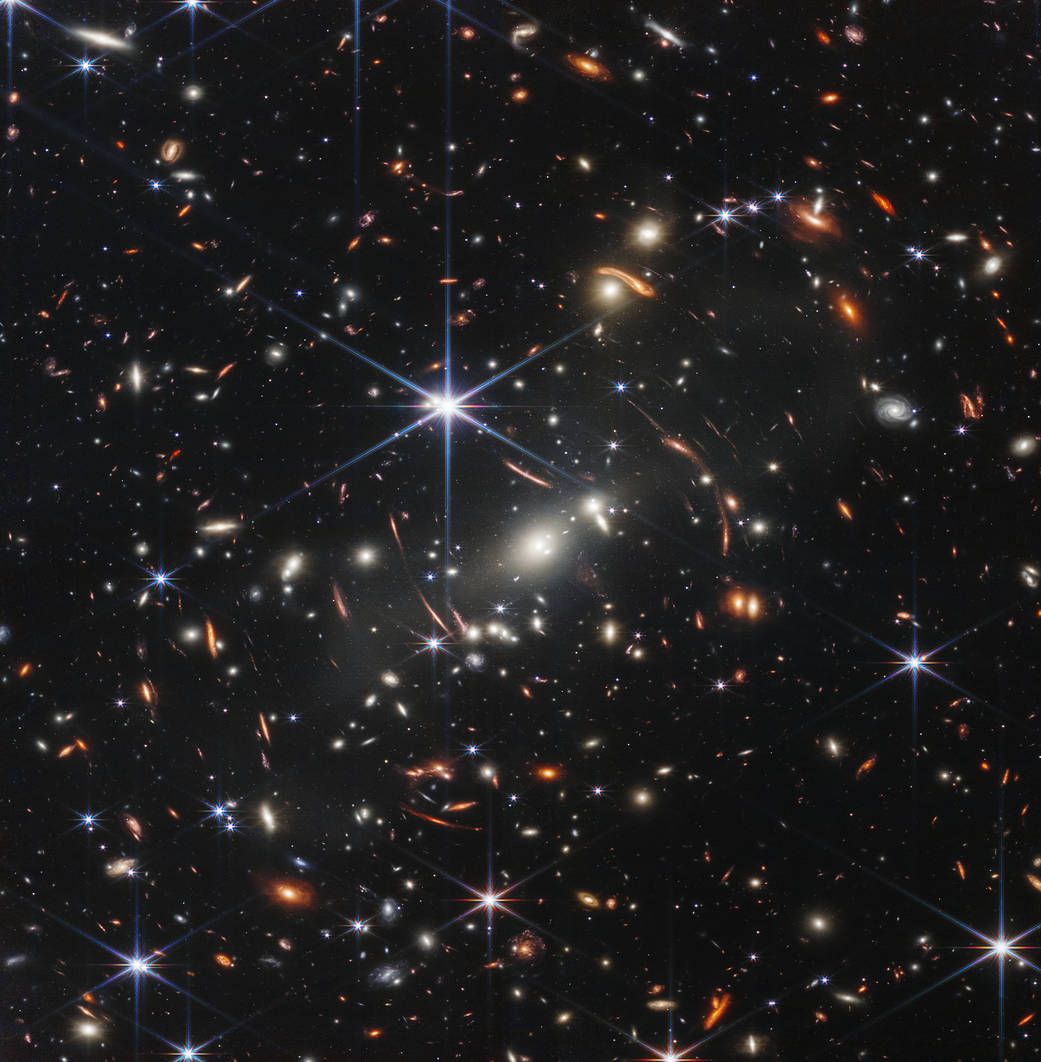

What you’re about to see is our “deepest, sharpest”, and best look at the cosmos yet:

This is the farthest humanity has ever gone—4.6 billion years back in time, to be precise. That means the part of space you’re looking at in this picture is actually 4.6 billion years-old and does not represent how it would look like today. This is because these places are so astronomically far away that it takes light billions of years to even reach here, which enables us (aka the telescope) to then capture the picture.

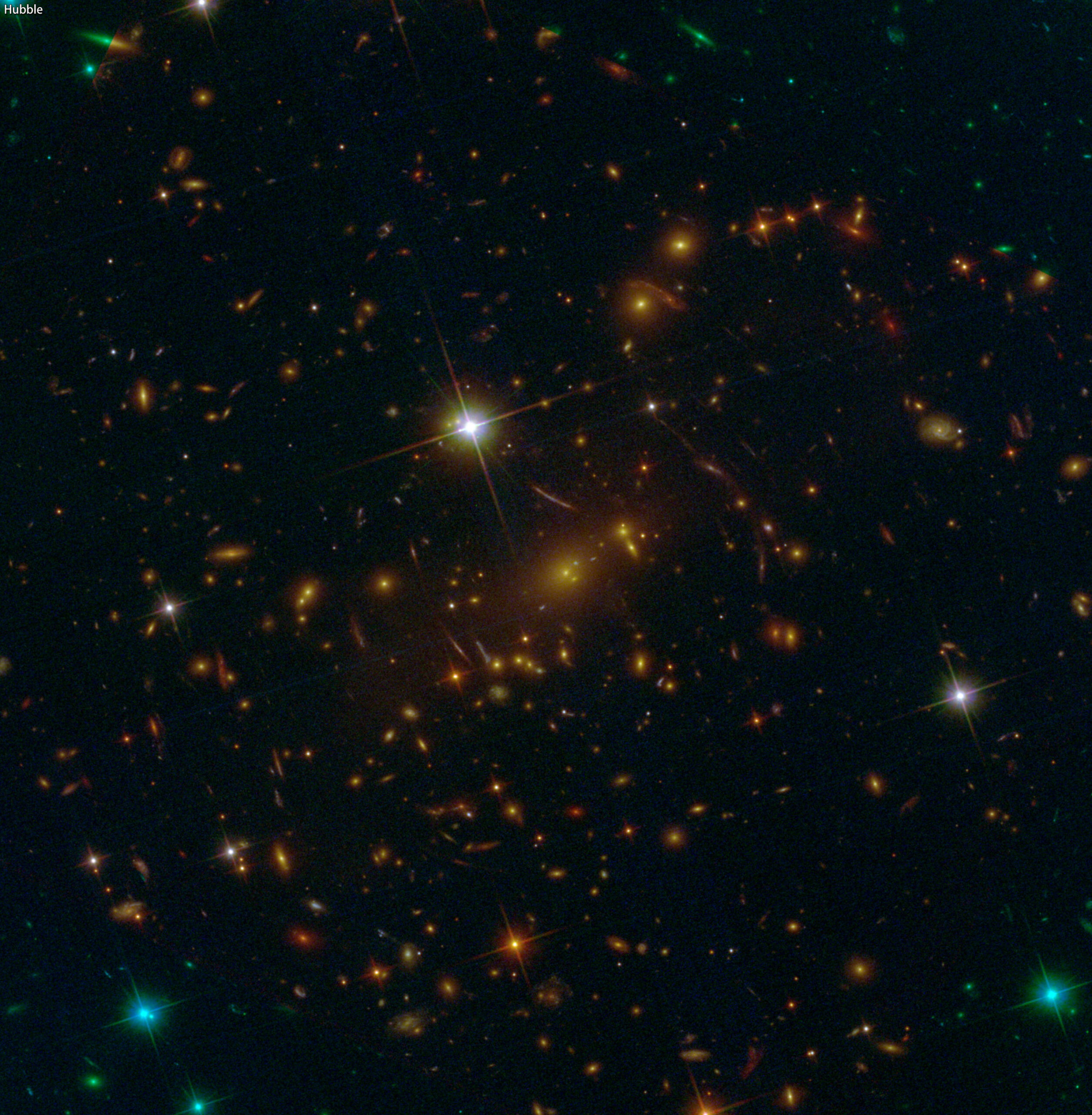

Essentially, the JWST is looking back in time, just like its predecessor. Hubble was able to go as far back as 13.4 billion years when, in 2016, it found the light wave signature of an extremely bright galaxy. For context, the Big Bang Theory states that our universe was created 13.7 billion years ago.

Webb can see backwards in time to just after the Big Bang by looking for galaxies that are so far away that the light has taken many billions of years to get from those galaxies to our telescopes. – Jonathan Gardner, Webb’s deputy scientist

What we’re seeing

Looking at the picture in question, it shows the SMACS 0723 galaxy cluster, as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago. However, the faintest streaks of light seen here are much, much older. Due to some of the galaxies in the picture being as old as they are, they partake in a phenomenon known as ‘gravitational lensing‘.

In simple words, gravitational lensing occurs when space is bent around certain astronomical objects, due to gravity. Gravity also, thus, bends light. This causes structures that are even further away behind to get magnified as a result of the lensing. That’s how we’re able to see light in the background which is actually older than the light in the foreground.

Every single object in this picture that doesn’t have a lens flare is a galaxy, while everything else is a star. Those weird arcs and smudges of light that appear to have a bright orange/red hue are the streaks of faint light I’m talking about; they’re the product of gravitational lending. They’re actually not there in reality, just enlarged by the space bending around the galaxies in front of them.

In essence, the large cluster of galaxies in the front is creating a natural telescope of sorts in of itself, since it’s magnifying light. So we’re pointing the best man-made telescope at the best nature-made telescope to get a look at the oldest objects in the universe.

Therefore, galaxies, planets, stars, and other structures that are so far away that we could never see them, have now been brought into sharp focus for the first-time ever, taking us back over 13 billion years in some cases. What that means is you’re seeing the oldest recorded light in history of the universe. And it doesn’t even stop there.

We are looking back more than 13 billion years. […] That light that you’re seeing on one of those little specks has been traveling for over 13 billion years. […] We are going back almost to the beginning.

NASA administrator, Bill Nelson says that the JWST will go back as far as 13.5 billion years, almost to the beginning. There are more images in the pipeline that would show the universe even older than it looks in this picture, but they’ll be more focused on showing the specific parts of the cosmos rather than the bigger picture.

The technology behind the magic

Galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 has been captured multiple times before, but never to such a degree of precision and detail. James Webb telescope has helped produce by far the most accurate depiction of it to date. But, how did the telescope do it?

James Webb’s telescope uses infrared cameras to capture wavelengths of light beyond what the human eye can see. This allows it to parse through the clouds of dust and gas—among other anomalies—that obstruct all visible light. That’s how it was (partially) able to take a picture like this.

Infrared is part of the light spectrum that is invisible to the naked eyes; it can only be detected by specialized gear. And it just happens to be that infrared is where the really interesting science hides.

The structures seen in the picture above are so old that they bend space and time around them, as mentioned before. Mix that with our universe’s perpetual expansion, and the time it would take for literally reality-altered light to get to us, is increased even more. So, by the time we do see it, the light has stretched into the infrared spectrum.

And that’s exactly where the JWST’s highly-advanced camera system, titled “NIRCam” (Near-Infrared Camera), come into play. NIRCam uses a set of special lenses, prisms, and filters (even the gold-plated mirrors) to specifically read light that resides in the infrared part of the spectrum, recording data that is later tallied by humans on Earth.

What the JWST ends up capturing isn’t exactly presentable so the talented scientists work hard to compile the information into a picture that accurately represents that part of space. As such, the image you’re looking at is actually a composite of multiple different images taken by JWST at different wavelengths, in which the hue is manually added in.

The entirety of this recording process took about 12.5 hours (that’s regular Earth hours, BTW)—a task that took Hubble weeks to complete. That alone should give you an idea of the unprecedented technological breakthroughs the James Webb telescope has brought forward. And to think that this is just the beginning.

NASA will release the full set of JSWT’s first full-color images in a few hours and we’ll update the article when they do. However, it won’t be unreasonable to say that this image was definitely the highlight out of all, which is why it was previewed a day earlier.

Update: NASA has released some spectacular images showing a dying star, the new “Stephan’s Quintet” galaxy, and the formation of stars, and more. You can check out the entire image collection here.

Pictures like these are looked at milestones for humanity. Just three years ago, we saw the first-ever picture of a black hole that altered the course of space science forever, bringing us one step closer to understanding what lies beneath. With the James Webb telescope, NASA is expecting big things; revealing the secrets of the universe is just one of the entries on its to-do list.

You can check out the full-res image of the SMACS 0723 galaxy cluster captured by JWST in glorious detail here.