How to make a Program Executable from Everywhere in Linux

Most people install programs from the official package manager, so they don’t have to think about where they go in Linux. After installing them, they simply type the program’s name and it works like nobody’s business. What happens if you write your own executable shell script or you download a program from the Web? What if you’ve compiled something from source and it won’t run outside of a certain directory? Naturally, you should always make sure that every program is safe before you run it, but there are several ways to get it to run everywhere as soon as you have.

First off, you’ll need to be working at the command line. Search for the word Terminal from the Ubuntu Dash if you use Unity. Most desktop environments will allow you to open a terminal if you push Ctrl+Alt+T. Users of desktop environments like LXDE, Xfce4 and KDE can click on the Applications menu, point to System Tools and then point to Terminal. Though you usually need administrator access to work with programs, you won’t need to use sudo at all for this in most cases.

Method 1: Editing Your Path Variables

Assuming you know where the program is and it was already set to get executed, you can add it to your path. The search path tells bash where to look for the name of the program you type at the prompt. If you ever used the Windows or MS-DOS command lines, then you might remember this trick. Let’s assume that you have an executable in your downloads folder. If you want to be able to execute it from everywhere as long as your session remains open, then type export PATH=$PATH:~/Downloads and push enter.

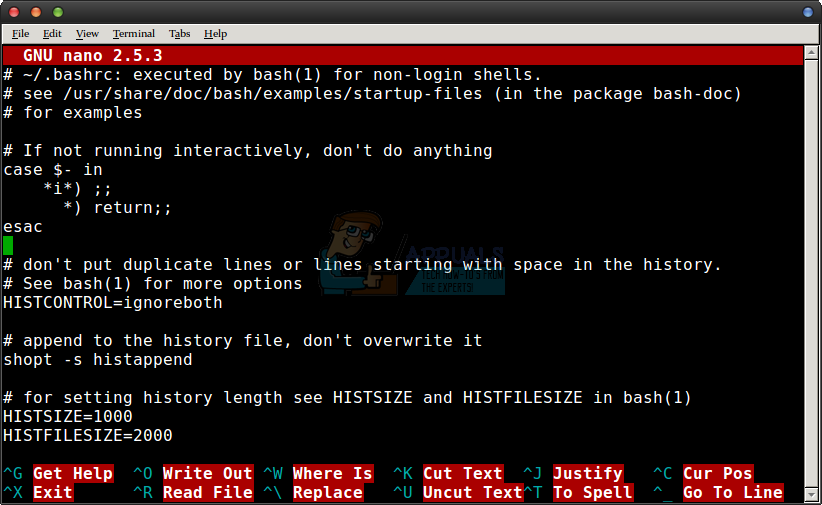

This will change the path for your current session, but when you open a new window or close the current one you’ll be back to your default path. Granted, that makes this perfect for times when you want to preform experiments but it isn’t ideal if you’re trying to get something permanent going. Type nano ~/.bashrc at the command line if you want to make a change for good.

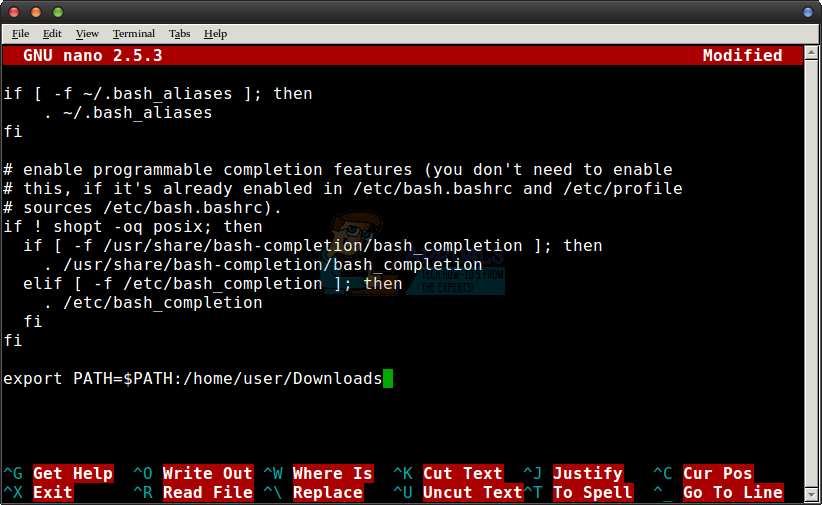

If you prefer a different editor like vi or vim, then you can replace the word nano in this command with the name of your favorite terminal text editor. Push the Page Down or cursor arrow down key to reach the bottom of the file and then add your path command. For instance, we added the line export PATH=$PATH:/home/user/Downloads at the bottom to make this a permanent location.

This will get parsed each time you open a new shell window. Keep in mind your user name is more than likely not user, so you’ll want to replace this. Push Ctrl+O to save it if you’re using nano and then push Ctrl+X to exit. You should be done, and For most users this is more than enough as this method involves the least amount of playing around. There are other paths you can take, no pun intended.

Method 2: Create ~/.local/bin Directory

While the ~/.local/bin directory is actually included in most default PATH assignments, it tends to not actually get created on many popular GNU/Linux implementations. Unless you’ve created it because you were making a shell script or something else that you wanted to run from everywhere, then you probably don’t have it just yet. That being said, since it got added by default programs will run out of it straight away.

At the command prompt, type mkdir ~/.local/bin and push enter. You shouldn’t see any output. If you get an error message that reads something like “mkdir: cannot create directory “/home/user/.local/bin” with perhaps a different name than user, then you simply already have this directory. You can safely ignore the error message if this was the case, because all it tells you is that you already have a directory and bash isn’t going to let you put another one on top of it.

Now anytime you move something into that directory, you should be able to run it from anywhere. Let’s suppose you have a shell script called chkFile in your Downloads folder that you’ve first checked to make sure was safe and wasn’t going to cause you any trouble. Naturally, this is merely a made up file name and you’ll want to type ls ~/Downloads or what have you to find the actual name. Assuming our example was right, you’d need to type chmod +x ~/Downloads/chkFile to make it executable and then type mv ~/Downloads/chkFile ~/.local/bin to put it in the right directory. From then on out, you should be able to execute it from wherever it is.

Method 3: Executing Programs Graphically

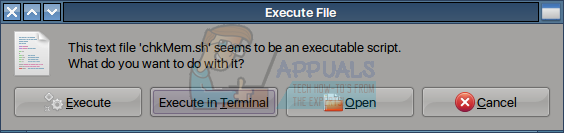

While many Linux users prefer to use the command line, you don’t have to execute scripts this way if you don’t want to. You do have other options. Pushing the Super and E keys in most graphical desktop environments will open up a file browser, or you could search for File Manager on the Ubuntu Unity Dash depending on the configuration you’re working with. You’ll be presented with a view of all the folders in your home directory, so double-click on the one that contains the executable you’re looking for. You can also highlight it and push the enter key.

Depending on your file manager, what happens next could be a little different. Some will automatically run it in a terminal or automatically start it as a program. Some, like PCManFM, which is included with Lubuntu, will give you a prompt.

This process is a bit clunkier and should only be done with files that you’re absolutely sure are worthwhile. That being said, this is a very useful way to start scripts while you’re authoring them and it might be something that gets overlooked by those who only ever work with the command line on a regular basis.